ACTF News

By James Dunlevie - ABC

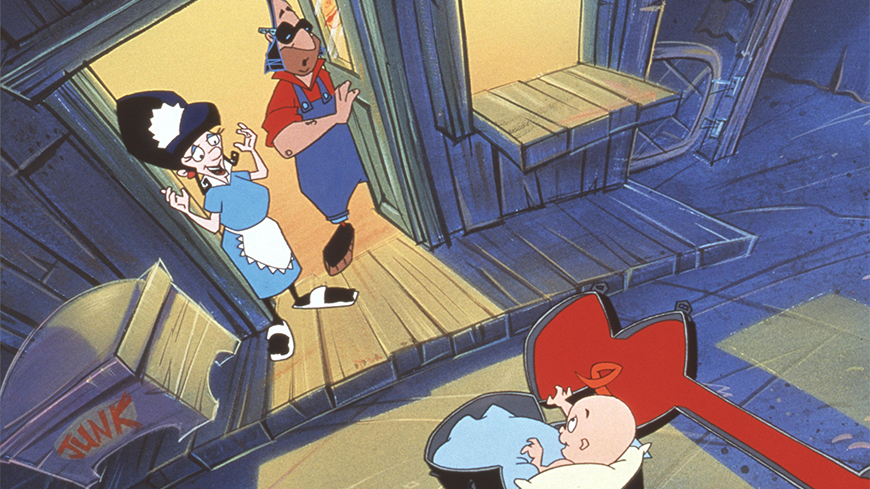

Decades before Bluey, an ambitious cartoon series featured Australian accents and humour, with an Aboriginal character front and centre — but Li'l Elvis and the Truckstoppers almost didn't get made.

The 1997 show, about the adventures of three kids in the Australian outback, was a bold undertaking — a totally original story concept, not a remake or an adaption of an existing literary classic.

While that seems rare today, consider this bizarre notion — it was decided to produced the series locally with people trained up from scratch, rather than having the animation done cheaply offshore.

One of the newcomers who landed a job on the series included three-time winner of the Gold Logie for Australia's Most Popular Television Personality — Rove McManus — who described his role on the production as constituting his "first 9 to 5 job", years before he would become a national celebrity.

Elvis Presley estate unimpressed

Born of the Keating Labor government's Distinctly Australian Program funding commitment to support "Australia's cultural industries", the series was commissioned by then Australian Children's Television Foundation (ACTF) boss Patricia Edgar on a mission to "find a marketable idea".

"We advertised widely through film organisations and in the trade press and received twenty-six applications — most of which were derivative, ordinary," Edgar wrote in her 2006 memoir.

The idea which stood out most was from Peter Viska, a Melbourne animator whose previous work included such titles as Far Out Brussel Sprout, Let 'er Rip Potato Chip and You Beaut Juicy Fruit!

"He had developed an appealing character called L'il Elvis," Edgar recalled. "I was an Elvis Presley fan and [ACTF producer] Susie Campbell thought I might be susceptible to the idea. But Peter's ideas were not viable.

"[Viska] thought we could acquire the rights to Elvis Presley's songs and animate each episode of the series around a song. I explained that the Graceland Estate would be unlikely to respond to an offer," Edgar said.

Viska tried his luck anyway.

"I wrote to Graceland and asked permission ... they wrote back and said 'no, you can't'," he said, laughing at the memory.

Campbell, with Viska's idea in her pocket, found herself in France at the Annecy festival, an international animation film market event.

"I got stuck in an elevator with the then-president of Universal Animation … bonded in adversity and with time to kill, we chatted. I took my chances at the dreaded 'elevator pitch' and said two words; Li'l Elvis. BOOM!"

Campbell, in a matter of minutes, had managed to sell the Li'l Elvis idea to Universal, the American giant of film and television. They would later pull out due to the Graceland legal difficulties — but, Campbell and Edgar could see they were on to a good thing.

What would eventually emerge, with the help of experienced writers such as Esben Storm (Round The Twist) and Chris Anastassiades (Lift Off), was the story — across 26 half-hour episodes — about a young Elvis impersonator with "a gift for music, a talent for trouble and a desire for only two things; to find out who he really is and be a normal kid again".

Li'l Elvis "spends his days entertaining truck drivers at his parents' roadhouse by playing Elvis Presley songs, but he is sick of the music and of his mum's insistence that he is 'the King' reborn" — Viska's nod to Michael Jackson "having his childhood stolen from him, being forced to get into a family band to make money".

It was a great idea — the trouble was that no-one had a clue as to how to make a cartoon series on such a scale in Australia, with Edgar confessing "animation was a production process I knew nothing about... It would be a learning experience for me and the whole team," she wrote.

They had a budget of $11.5 million with which to do it.

Lost in translation

With French and German production partners coming on board, there was more industry experience to draw on. But it also came with more problems.

"Our writers did not understand the process and everything needed to be rewritten," Edgar explained. "We also had to negotiate cultural differences as some ideas that we found funny were offensive to the Europeans."

"I had never written animation before and was fairly new to writing children's television," Chris Anastassiades said. "My background was in situation comedy and a disastrous go at sketch comedy."

Anastassiades said Viska was "really clear" regarding his vision.

"It had to be funny, not just to kids but to a slightly older audience … there had to be much weirdness in each episode. It was a ton of fun."

A saving grace was that Viska had found, through the French, a designer and director who would prove instrumental in helping the show achieve its uniquely Australian look — ironically, a Belgian.

Animation designer and director Jan Van Rijsselberge "had learnt his English from (1980s Australian television series) Sons and Daughters, watching it in Belgium in English," Viska said.

The series was "my first big break," Rijsselberge said. "My role consisted in modernising the look whilst keeping the Aussie feel of the world."

Van Risselberge also remembered the foreign partners' bewilderment over the stories.

"The scripts were written for an Anglo Saxon audience — a mix of adventure, sitcom and slapstick — a style which was hard to comprehend for the French producers," he said.

No such thing as 'too big'

As for the characters, the ACTF was "really aware of the social responsibility of casting Aboriginal people as Aboriginal voices," Viska said, with the Aboriginal character of Lionel Dexter played by Indigenous actor Kylie Belling.

"Kylie was really important, she was fabulous," he said.

Other voices included David Cotter (Len Jones), Bill Ten Eyck (WC Moore), Michael Veitch (Duncan), Marg Downey (Janet Rig), Stig Wemyss (Li'l Elvis speaking voice), Nick Giannopoulos (Hector) and the late comedian Lynda Gibson (Grace Jones).

Rock performer Wendy Stapleton was picked to play Li'l Elvis, as well as provide vocals on the show's many musical numbers — until the producers had a change of mind.

"I landed a role as someone doing lots of bit parts, additional characters," Wemyss recalled. "At the end of the first read-through the producers and director pressed the button in the booth and asked, 'Stig, would you mind sticking around'?"

Stapleton would remain as the singing Li'l Elvis, with Wemyss handling the spoken parts — with much effort going into matching the pair's voices in transitional scenes which switched from speaking into song.

Voice cast recording sessions were deliberately done with the actors all in the same room, Viska said — "all trying to outdo each other … ego versus ego", getting just the result the producers wanted.

"There was no 'too big'," Wemyss said of the group recordings. "It was awesome fun. We all felt we were doing something special."

US actor Bill Ten Eyck, who had already played an American "looking to buy Ramsay Street" on Neighbours, took his inspiration for billionaire WC Moore's broad Australian accent from comedian Max Gillies — with a dash of Lionel Barrymore's character from It's A Wonderful Life.

The Li'l Elvis cast were "some of the funniest people I've ever had the pleasure to work with," he said. Ten Eyck would go on to supply 15 voices across the series.

'I wasn't sure how it would work'

A crucial part of the show was the music, which Peter Viska imagined as "rockabilly, but with a didgeridoo".

Tony Naylor, a veteran session guitarist whose work included "both Crocodile Dundees and the Alvin Purple films" got the gig of bringing the sound of "didgerbilly" to life.

"I was intrigued … but at first wasn't sure how it would work musically, combining the rockabilly chordal changes with didj drones," Naylor said.

The late Aboriginal actor and musician Tom E Lewis provided the soundtrack's didgeridoo.

"We wrote the tracks with didj samples as a guide … then [Lewis] took it to a whole other level of expression."

The sound recordings in the bag, at least that part was done. The real trick would be bringing Li'l Elvis alive on the screen — with a team mostly made up of people who had never worked in animation before.

'Steep learning curve'

2D animation, the kind involving hundreds of painstakingly hand-drawn images that make up sequences, is typically one of the most expensive forms of screen entertainment.

In 1996, most cartoon series were still 2D.

Computer generated imagery (CGI) 3D animation on an episodic television series level was still far off — and the computerisation of in-betweening was also in its early stages.

2D animation, as popularised by Disney, Warner Brothers and Hanna Barbera, was still king — and due to the amount of human labour, cost a fortune to produce, which made the decision to employ a team of largely inexperienced people to produce Li'l Elvis — the equivalent of around 11 hours, or over seven feature-length films, of animation — even more remarkable.

The production workforce simply did not exist at the time in Australia.

In keeping with their act of faith, the producers set up in a disused convent in Albert Park, Melbourne. There, Viska and the producers would rely on some older pros, to guide the newbies.

"The ACTF decided to build a studio from scratch for L'il Elvis, meaning a very steep learning curve for a very young and inexperienced team," Van Rijsselberge said.

Robbert Smit, whose work had included Blinky Bill, Footrot Flats and The Magic Pudding, was put in charge of the animation and told to pick around 90 artists from the "500 portfolios dropped on my desk".

"We were three months behind schedule and had to sink or swim. But swim we did," Smit said.

Andi Spark was Smit's assistant director and recalled the determination to "make this on site, in Australia, training up people for the industry".

Joining the 90 new artists would be a handful of seasoned key frame animators, along with 39 trainees and in-betweeners — artists who complete the "in between" drawings, using the key frame illustrations as a guide.

Having over 100 artists all draw a character the same way, consistently and without variation, proved difficult, Spark recalled — with the term given to describe characters which have gone wrong somehow as being "off model".

"Having a neurotically keen eye for detail was essential to spot things like missing buttons, back-to-front stripes, off-model noses, et al," she said.

For the series' background art, it would be another foreign eye which would help capture the look the producers wanted.

"I came from the Czech Republic," said veteran artist and illustrator Richard Zaloudek, who like Smit had worked on Footrot Flats. "The European landscape is like a postcard, but you come here [to Australia] and the light is so different, the vastness, the red soil," he said.

Despite the "crazy workload … hoping I didn't get sick, I had no assistant" Zaloudek describes his Li'l Elvis experience as "a wonderful time", saying of Viska "considering he never worked with me before, he trusted me completely".

Rove's first 9 to 5

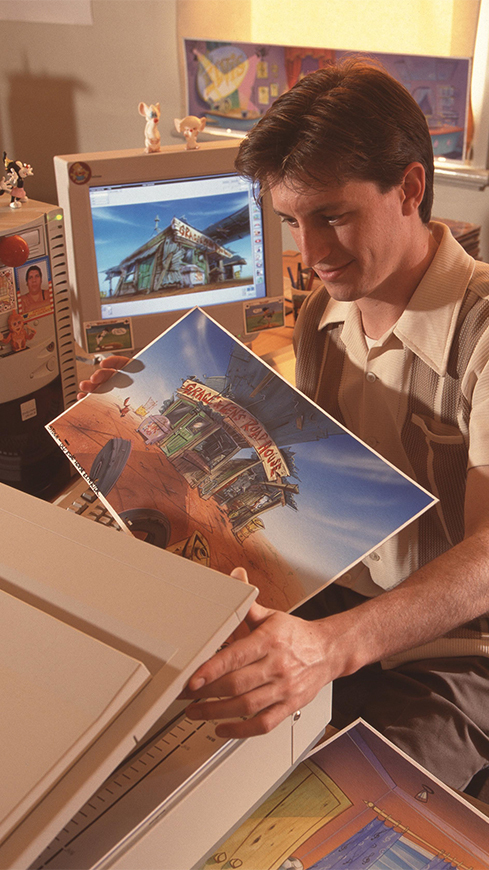

One of those who joined the Li'l Elvis team was Rove McManus, who had come to Melbourne from Perth to pursue a career as a comedy performer.

"I saw an ad in the Melbourne street press, they were looking for animators," McManus said. "I gave them a call and asked if there was a chance I could do a voice role, but they had long before been cast and recorded."

Still, he persisted, convincing the producers he would be an asset in whatever role they could give him.

"I really cared, I was really invested in the show, I was passionate about animation and wanted the series to succeed," he said.

McManus said at the time the Li'l Elvis production was beginning "I had only been in Melbourne a year or so".

"I had not had a regular day job, I had only been a performer, that's when I learnt what coffee was, working during the day [on Li'l Elvis] and performing at night."

For much of the series, McManus was working with painted backgrounds and animation cels, using a flatbed scanner to import thousands of images into what was at the time a state-of-the-art computer system. "I'd sit there for ages trying to get the colour balance right," he remembered. "It wasn't great technology."

By the late 1990s, image-scanning technology had improved, but still struggled to capture the beautifully painted scenes, with their wide range of reds, oranges, yellows and violet hues.

"One day, when I didn't do a good job of it, Peter Viska came in and got very mad at me, holding up the original background against the screen," McManus said.

After that dressing down, "I worked hard and got it right", he said — figuring out through trial and error what worked and what didn't, keeping a notebook of scanning settings to achieve the desired result.

It worked — and perhaps impressed the producers just enough to allow him to voice a character in the Monkey Sea, Monkey Doo episode.

McManus would go on to become a successful comedian, television and radio presenter and producer, winning three Gold Logies — the award for the most popular personality on Australian television, as voted by the public.

Plug pulled

Producer Susie Campbell said by the end of season two, "we all just needed a rest".

"Li'l Elvis was an animated drama series. It was not developed as an ongoing cartoon, but as a full drama with a story arc over the 26 episodes that had a start, a middle and an end. Ongoing cartoon series, as opposed to animated dramas, were not eligible for Australian funding at the time.

"The ACTF did not see its role as continuing in animation production, more so as forging a market for it and then stepping back."

For those who learnt their craft on the show, the experience of working on Li'l Elvis still holds fond memories.

Mark Sheard, the youngest trainee in the Li'l Elvis team, still works in animation.

"It's still the best production and community I have ever worked with. I guess that's why I'm still here, chasing that dream to work with so many amazing people again," he said.

Ariel Waymouth, who started at Li'l Elvis as an animation checker, stayed in the industry and is now with VicScreen as a production executive focused on children's content.

"I also had to count the frames for each scene daily and calculate each animators' quota," she said. "I heard every excuse there was to why a scene wasn't finished … and yes the dog did eat a folder once."

Current chief executive of the ACTF, Jenny Buckland, said Li'l Elvis was a game changer. "It was popular at the time and demonstrated that Australian landscapes and accents in animation would appeal to Australian kids, but I think we are only just beginning to realise the impact of this.

"We're finding that many of the people working here in animation today … were inspired by Li'l Elvis growing up. They seemed to absorb that it had been made here, that it was somehow different to a lot of the other animation they were watching, and this has inspired a sense of believing they might follow a creative path."

Andi Spark, who would later help set up the studio which would produce international smash hit Bluey, said the blue dog owed Li'l Elvis a debt.

"Bluey's certainly been one of the most successful shows ever to come out of Australia, but I reckon Li'l Elvis really laid the foundation for that in being the first wholly original written for TV animated series from a distinctively Australian perspective."

Bill Ten Eyck said a show like Li'l Elvis would simply not get made today and is scathing of the current level of support for the Australian arts, saying "consecutive governments" have "waged an ideological jihad" on the sector.

"The short-sightedness regarding the destruction of the local arts industry is the saddest thing I've seen in 30 years," he said. "These days I am a teacher [of drama] … how do I tell kids they should go into the arts?"

You can view episodes of Li'l Elvis and the Truckstoppers on our Twisted Lunchbox YouTube page here.

This article was originally published on ABC News Online. Republished with permission.